Blogs | 3.21.2023

Engaging Students in Diplomacy: A Necessity for Our Future in Space

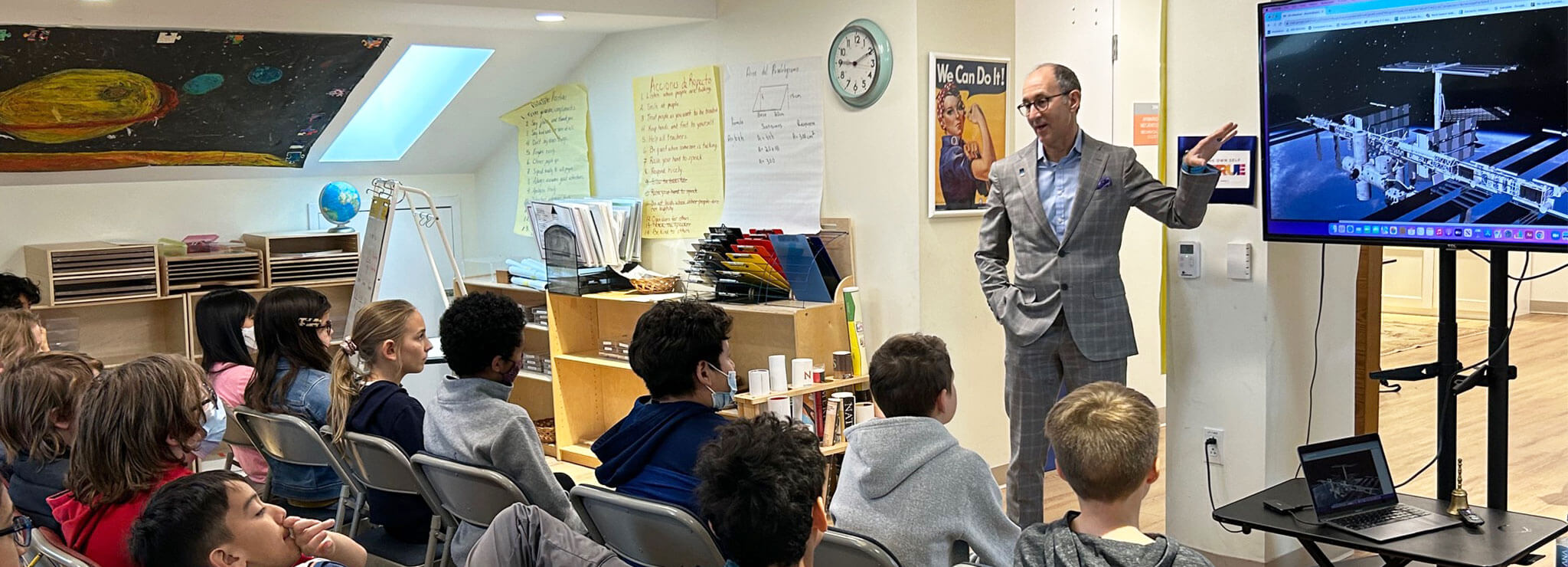

Earlier this month, I met with 28 students at Latin American Montessori Bilingual Public Charter School (LAMB PCS) in Washington, D.C. I was invited by Ms. Dolores Peck, a 4-5th grade teacher, to speak with them about diplomacy. She recently assigned her class to work in teams to create an imaginary island and wanted them to consider how they work with other island nations to trade goods and services, and how to ensure their population’s security. At Challenger Center, we inspire and engage the next generation of innovators and explorers . . . teamwork, which involves diplomacy skills, is a skill we teach in our programs.

Diplomacy in Space

Prior to becoming President and CEO of Challenger Center, I was a diplomat, representing NASA in negotiations with foreign space agencies to agree on terms for the commercial use of the International Space Station (ISS). The ISS and all the space stations in development could be considered islands in space.

The students were aware that I was also recently invited by Vice President Kamala Harris to join the National Space Council’s (NSC) Users Advisory Group (UAG), a team of leaders and experts that advise the U.S. on space policy matters. I described the Exploration and Discovery Committee (the committee I chair) and shared that representatives from several of our country’s largest companies involved in space exploration are also members. I encouraged everyone to research these companies—Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman, United Launch Alliance, SpaceX, and many more represented by the Commercial Spaceflight Federation—and imagine how they can work for them one day.

One major issue important to the UAG is the need to better regulate how countries deploy and manage objects in low Earth orbit (LEO). LEO is becoming cluttered with satellites and debris, which impacts the ability of any government or company to launch rockets and to create societal benefits by obtaining real-time images of Earth used for environmental and security purposes, as well as communications, GPS services, and many more important services to people around the globe. Like the Moon, no one “owns” LEO. So, how do we work with countries to make rules about how we share that space?

The answer is diplomacy.

Who Owns the Moon?

The students were ready to dive into the conversation. Drawing upon knowledge gained from past projects about the solar system and artificial islands, they fired questions and ideas at me for almost an hour:

- How do we share space on the International Space Station?

- If we go to the Moon and mine for minerals, won’t other countries want to do that too?

- Who owns the Moon?

- If we found alien life in space, how would we communicate with them? Would you be a diplomat and try to negotiate with them too?

While I was professionally trained to lead diplomatic negotiations by the U.S. Foreign Service, I shared the simple key to good diplomacy: Approach the people with whom you want to negotiate as partners, not adversaries. Assume good intentions. Get to know them as individuals. Treat them with respect. Listen carefully. Be humble and kind.

With this, Ms. Peck pointed to a sign in the classroom that listed the exact same rules for the students’ collaborations with each other.

As always, my interaction with these students left me feeling good about the future. Students often see the world more clearly than we grown-ups expect. They focus on possibilities more than barriers. They have big hearts and want to be involved in meaningful societal goals. It’s up to us to prepare them for the future. Being a good teammate and using diplomacy skills will be essential.